The Arabic alphabet and long vowels are the focus of this lesson. In previous lesson, you learned the Arabic letters and their pronunciation which varies according to the short vowels (al-ħarakaat al-qaSiirah, الْحَرَكَاتُ الْقَصِيرَة) that accompany them. For example, we pronounce the letter ل as لَ la, لِ, li, or لُ lu. What if long vowels follow the letters, to what degree their pronunciation differs.

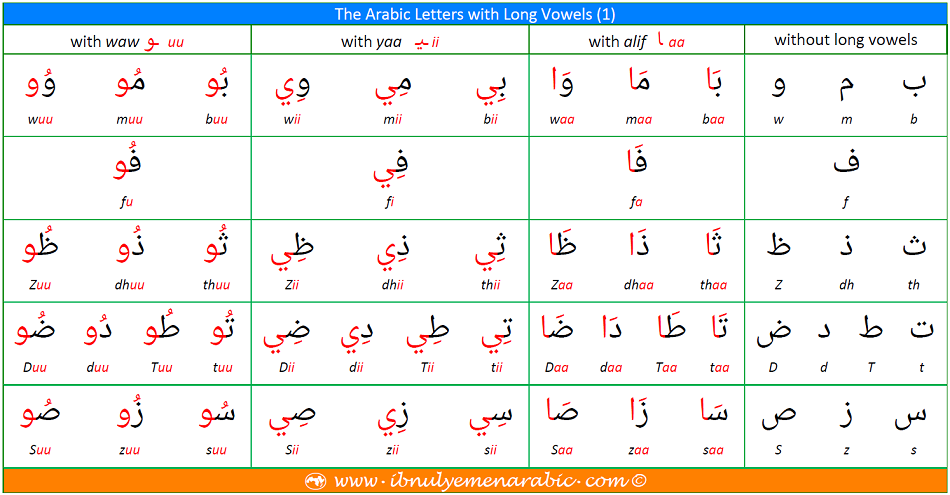

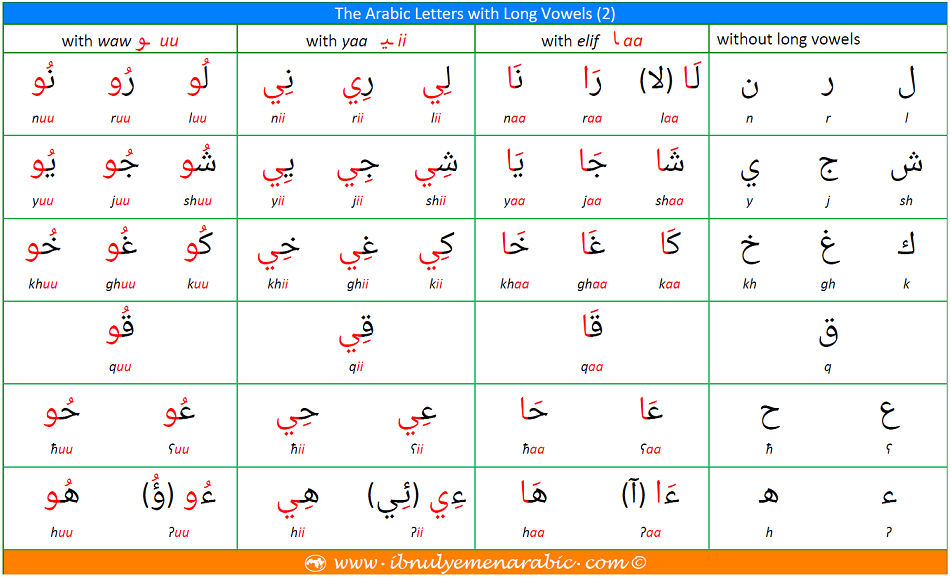

If the long vowels (al-ħarakaat aT-Tawiilah الْحَرَكَاتُ الطَّوِيلَة) follow the letters, their pronunciation remain relatively similar. The difference is in the lengthening of the short vowel. For example, the pronunciation of ب with fatħa (بَ) is ba. If the long vowel (ا) follows the ب, (i.e., بَا), its pronunciation becomes baa. Likewise, بِ bi becomes بِي bii, and بُ bu becomes بُو buu. And so is the case with the remaining letters, as in tables (1) and (2).

As you can see in the tables, the long vowel always triggers the appearance of the corresponding short vowel on the preceding letter, hence the alif triggers the fatħa, as in سَا, بَا, and مَا; the yaa’ triggers the kasra, as in سِي, بِي, and مِي; and the waaw triggers the Damma, as in سُو, بُو, and مُو.

The hamza ء is written as آ when it is accompanied by fatħa and followed by alif ـا; as ـئـ when it is accompanied by kasra and followed by yaa ي; and as ؤ when it is accompanied by Damma and followed by waaw و. You will learn more about the hamza here.

You may be wondering what the difference between the hamza ء and alif ا is. The hamza can be accompanied by the short vowels, while the alif is not; that is, it (the alif) is always saakin. That is, it is accompanied by sukuun (sukuun = the absence of short vowels).

In the next lesson, you will get to know how to join these letters cursively to form Arabic words.