Arabic diacritics are vocal letters, i.e. marks, signs, or symbols. Put differently, they are not written letters. Therefore, Arabic letters indicate consonants and long vowels only. Linguistically, vocal letters do not exist in many world languages. In such languages, the vocal letters are part of the alphabetic system. That is, they are the vowel letters that we see in English and Latin-based languages. So, what are the Arabic diacritics?

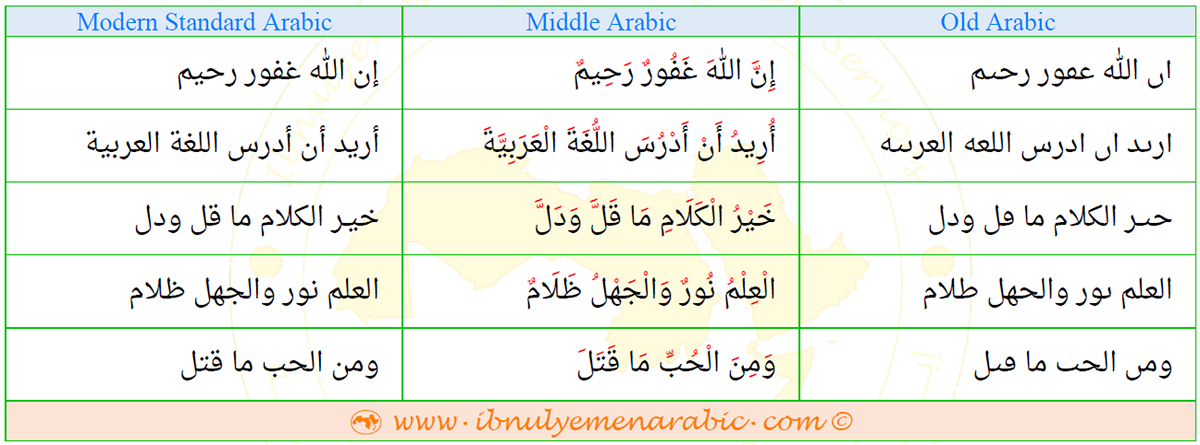

In the first column of the table above, under Old Arabic, this is how written Arabic was during the first few decades of Islam. The Arabs (between 30 and 50 men) in Mecca and Madinah wrote Arabic without dots or diacritical marks. Using their intuition and the context, they could read this form of Arabic with ease. That is, they encountered no problems with homonymy and polysemy (i.e., multiple pronunciations and meanings of the same word(s)). More importantly, they were able to assign the proper Iʿrāb (إِعْرَاب), i.e. the correct word-final diacritics. All of this is attributed to their innate knowledge of the Arabic and/or natural language instinct.

In the second column, under Middle Arabic, the Arabs added the dots and diacritics. This initially emerged during the second half of the first century of Islam. When many non-Arabs embraced Islam and moved to Basra and Kufa in Iraq, corruption in Arabic language became widespread. This greatly affected the meaning and the understanding of the Holy Quran. As a result, the ruler of Basra at the time ordered Abu al-Aswad ad-Du'ali, who was knowledge in Arabic language, to add the proper Iʿrāb to the Quran which he did. The first form of word-final diacritics (Iʿrāb) was dots (above the letter, below the letter, or next to the letter).

Towards the end of the first century of Islam, people encountered difficulties with homonyms and homographs (i.e., words with the same spelling but different pronunciations and/or meaning). Iraq was the main area of Arabic language corruption as it was close to Persia and Anatolia from which most new embracers of Islam came. Therefore, al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf, the ruler of Iraq at the time ordered that some form of marks/symbols that distinguished similarly-shaped letters be added. Two Arabic language experts, who were students of Abu al-Aswad, added dots (one, two, or three) over or below similarly-shaped letters. To distinguish these dots from the dots of the Iʿrāb, they were in red.

During the first half of the second century of Islam, the coloring of dots presented some difficulties for the inscribers of Arabic language as they were to write more texts, and some were in remote areas. As a consequence, al-Khalil ibn Ahmad al-Farahidi, a leading grammarian, proposed a new form of diacritics that is different from the letter distinguishing dots. He called them the short vowels, and derived them from long vowels. He proposed the fatha from the alif, the kasra from the yaa, and the dhamma from the waaw. The shape of these diacritical marks resemble the long vowels. The fatha is a small alif lying down over the letter. The kasra is a small yaa (later became alif) lying down below the letter. The dhamma is a small waaw over the letter.

The form of Arabic under Middle Arabic exists today in children's books, some books of poetry, and most school textbooks. The Holy Quran includes all forms of diacritical marks and symbols. By so doing, readers of these texts will pronounce words correctly, and hence communicate and convey meanings effectively. Modern Arabic texts, on the other hand, are devoid of Arabic diacritics, as in the third column, under Modern Standard Arabic. So, can the Arabs read Modern Standard Arabic texts correctly even without the diacritical marks? The answer is yes, except for a few words that are homonymic and/or homographic (i.e., same spelling but different pronunciation and/or meaning). As for word-final diacritics or Iʿrāb, the vast majority of Arabs make mistakes. Only a small percentage of Arabs have and can develop this knack.

The next lesson will provide more specific information about Arabic diacritics.